April 23: Full Pink Moon and Spring Triangle

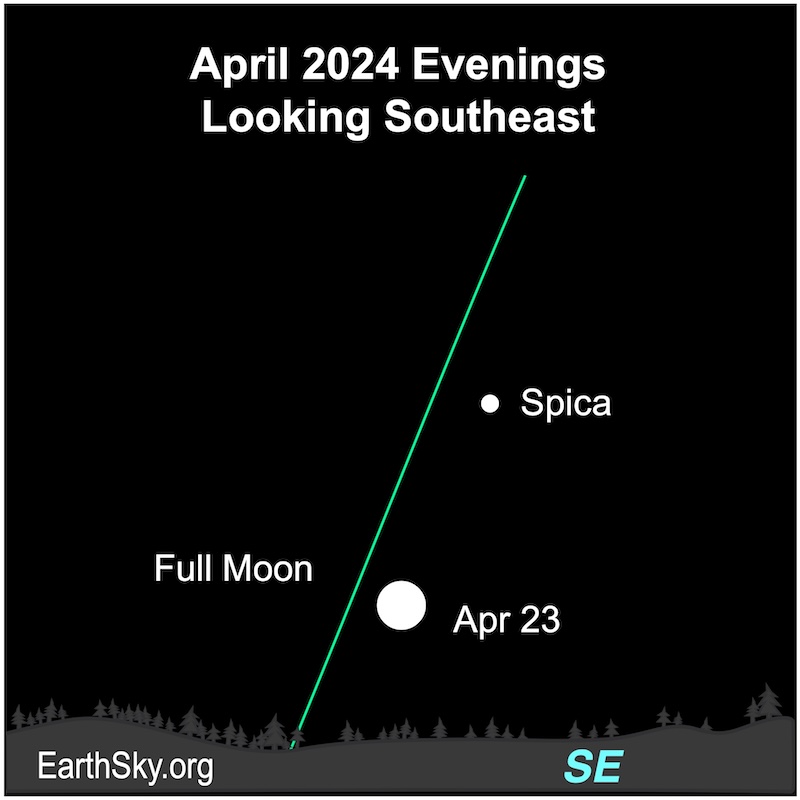

April 23: Full moon near Spica

The full moon will glow brightly near the bright star Spica in Virgo the Maiden. Full moon occurs at 23:49 UTC (6:49 p.m. CDT) on April 23, 2024. It’ll be visible all night.

Our charts are mostly set for the northern half of Earth. To see a precise view – and time – from your location, try Stellarium Online.

See a 1-minute video about the phases of the moon in April

Want to know about moon phases for April? Join EarthSky’s Marcy Curran for a 1-minute video tour of the moon phases – and dates when the moon visits planets in our sky – in this EarthSky Minute.

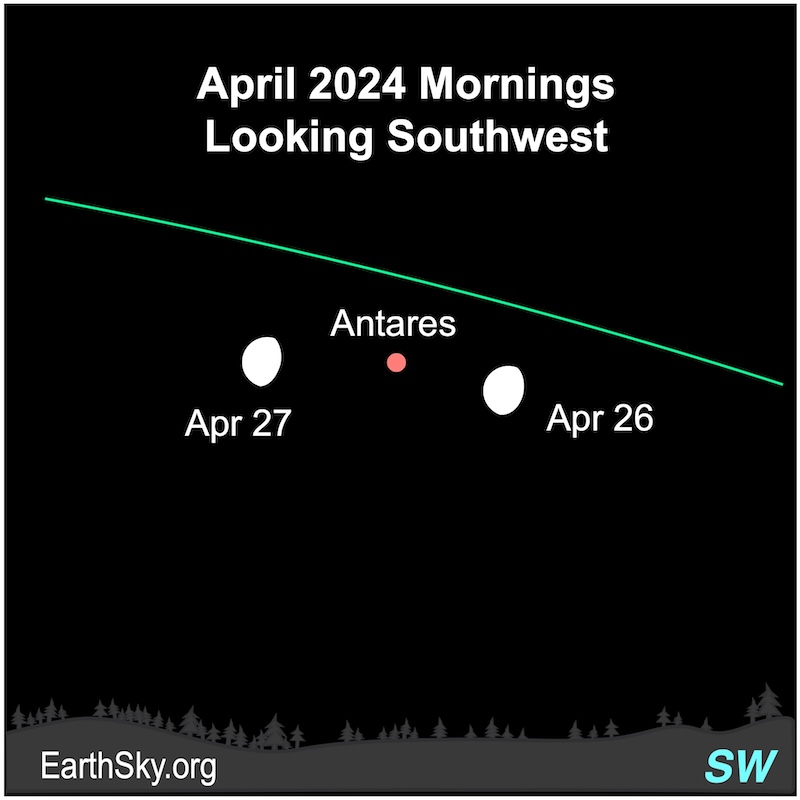

April 26 and 27 mornings: Moon near Antares

On the mornings of April 26 and 27, 2024, the waning gibbous moon will lie close to the bright star Antares in Scorpius the Scorpion. They’ll be visible from early morning until dawn. Also, skywatchers in Asia and Africa will see the moon pass in front of – or occult – Antares near 21 UTC on April 26.

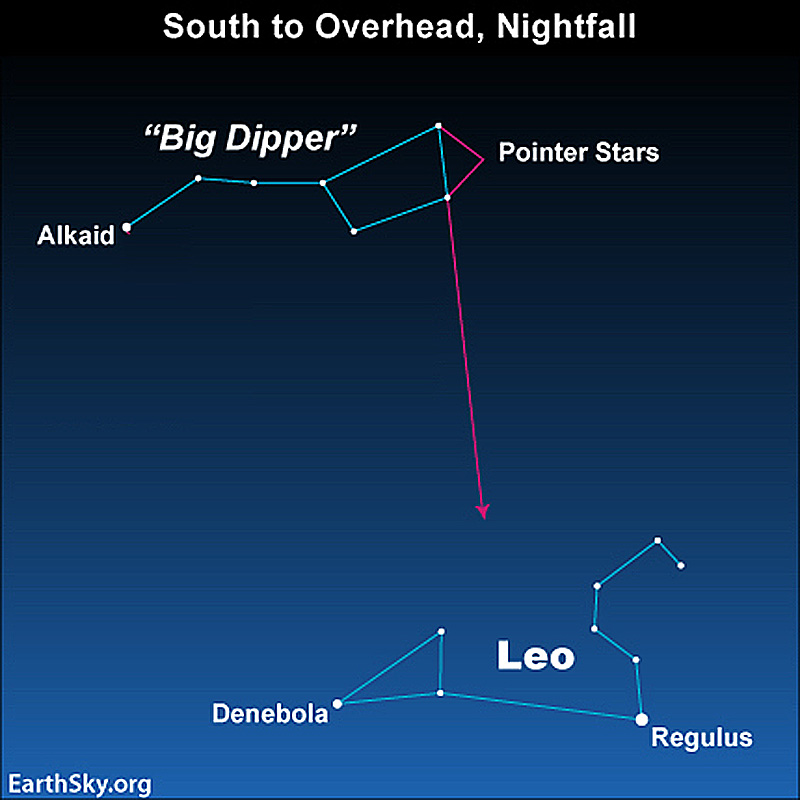

The Big Dipper and Leo the Lion

April is a great time to look up overhead in the evening sky and find the well-known pattern of stars we call the Big Dipper. It’s an asterism – or obvious pattern of stars – and part of the constellation Ursa Major the Great Bear. Also, you can find the constellation Leo the Lion. Leo has another well-known asterism known as the Sickle. The Sickle looks like a backward question mark that is punctuated by the bright star Regulus. In fact, the Big Dipper can help you locate Leo and the Sickle. An imaginary line drawn southward from the pointer stars in the Big Dipper – the two outer stars in the Dipper’s bowl – points toward Leo the Lion.

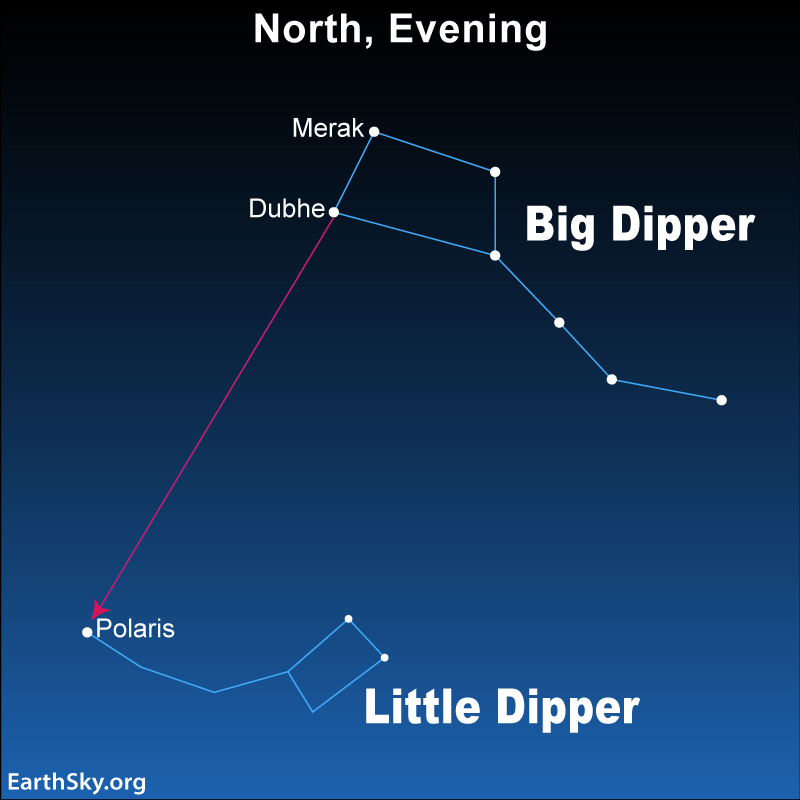

The Big Dipper and Polaris

Plus, the Big Dipper can direct you to find Polaris, the North Pole Star. The two outer stars in the bowl of the Dipper point to Polaris. It’s at the end of the handle of Ursa Minor the Little Bear, commonly known as the Little Dipper. Look for the Big and Little Dippers high in the northern sky on spring evenings. This view is for the Northern Hemisphere.

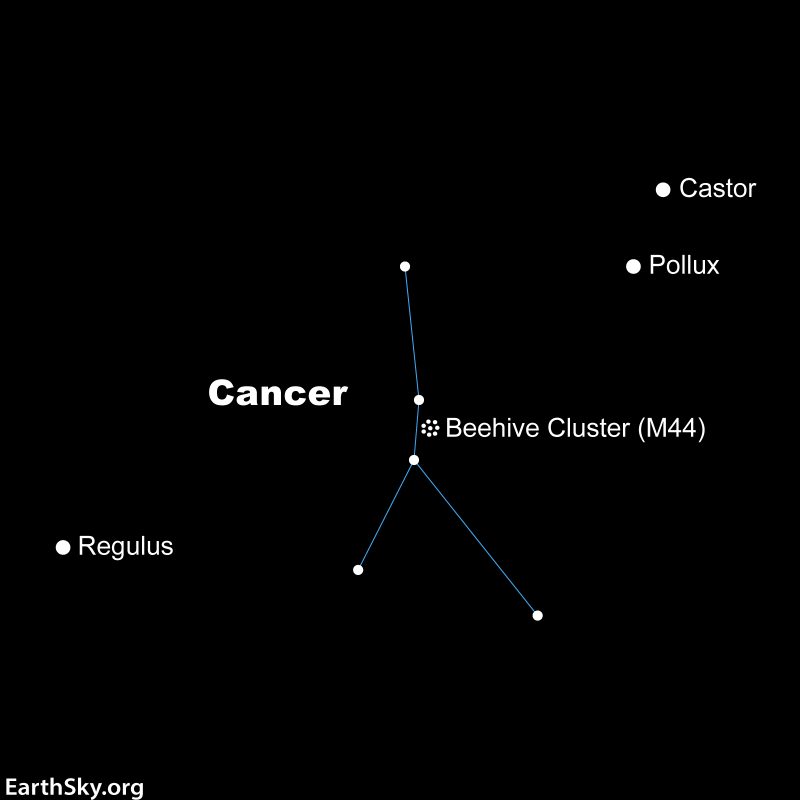

Cancer the Crab

Cancer the Crab, with its Beehive star cluster, needs a dark sky to be seen. It lies between the Gemini twin stars Castor and Pollux, and the bright star Regulus in Leo the Lion.

Once you’ve found Cancer – if your sky is dark – you can see the wonderful open star cluster called the Beehive. It contains some 1,000 stars.

Have fun exploring the sky!

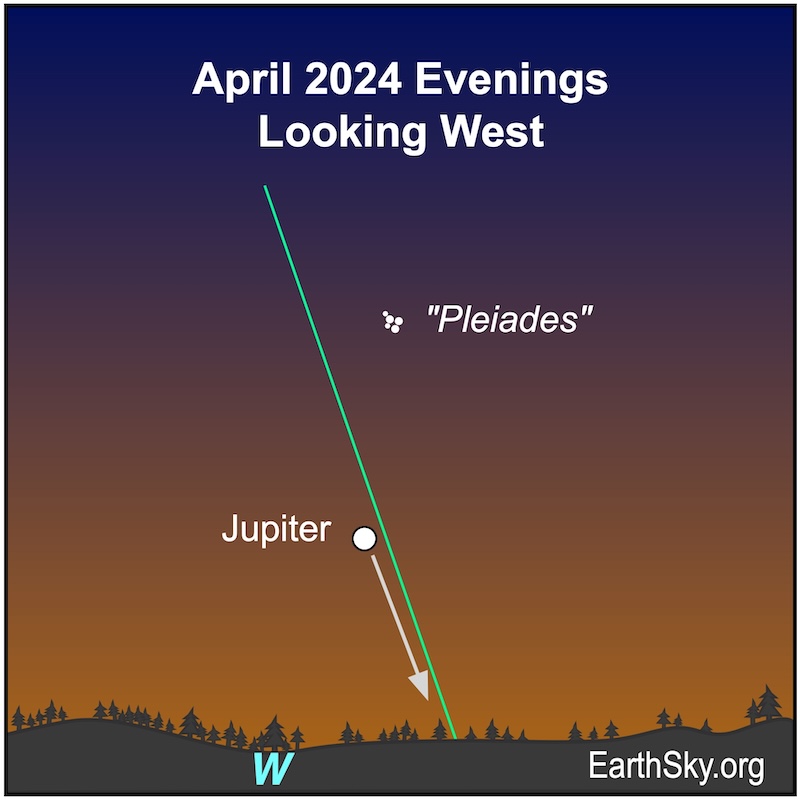

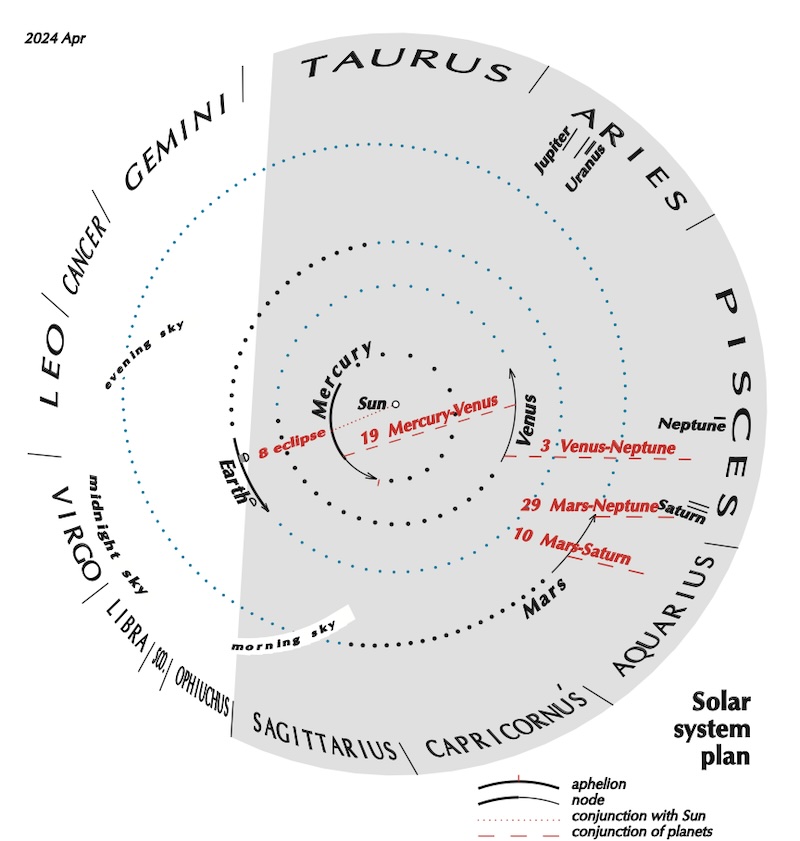

April evenings: Jupiter

Jupiter appears low in the west shortly after sunset in the first three weeks of April. During the month’s final week, it lies too low in the bright evening twilight to be easily seen. At the beginning of the month, Jupiter sets about three hours after sunset. At month’s end, Jupiter lies low in the evening twilight and may be challenging to spot. Jupiter will lie near the delicate Pleiades star cluster.

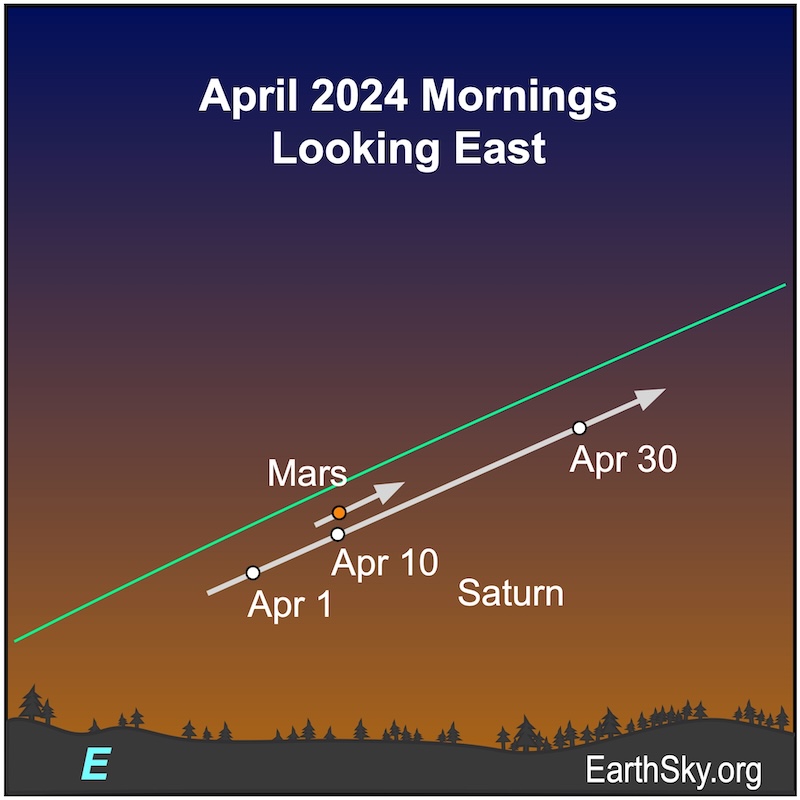

April mornings: Mars and Saturn

Mars and Saturn lie low in the morning twilight in April 2024. They shine with similar brightness and have a close pairing on the mornings of April 10 and 11. Saturn will climb a bit higher as the month goes on, and Mars will not move as much on the sky’s dome. By month’s end, Saturn will rise about two hours before sunrise and Mars will follow it about an hour later. Both planets will be easier to find in the coming months as they climb out of the morning glare.

Where’s Venus and Mercury?

Venus is too close to the sun to be visible this month, and it’ll emerge in the evening sky around the beginning of August. Mercury will disappear from the bright evening twilight at the beginning of April and return to the morning sky in May.

Thank you to all who submit images to EarthSky Community Photos! View community photos here. We love you all. Submit your photo here.

Looking for a dark sky? Check out EarthSky’s Best Places to Stargaze.

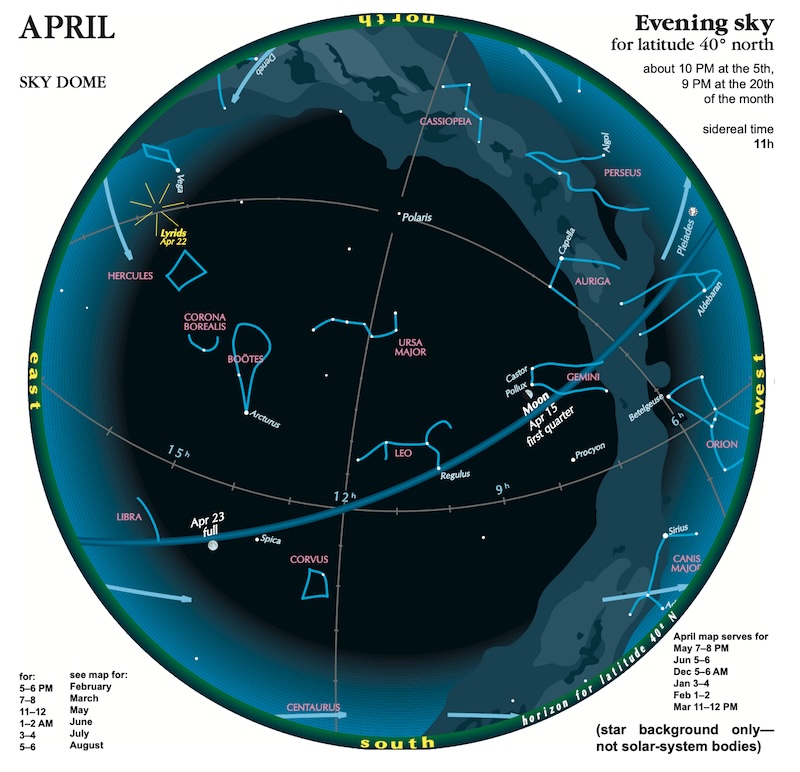

Sky dome maps for visible planets and night sky

The sky dome maps come from master astronomy chart-maker Guy Ottewell. You’ll find charts like these for every month of 2024 in his Astronomical Calendar.

Guy Ottewell explains sky dome maps

Heliocentric solar system visible planets and more

The sun-centered charts come from Guy Ottewell. You’ll find charts like these for every month of 2024 in his Astronomical Calendar.

Guy Ottewell explains heliocentric charts.

Some resources to enjoy

For more videos of great night sky events, visit EarthSky’s YouTube page.

Watch EarthSky’s video about Two Great Solar Eclipses Coming Up

Don’t miss anything. Subscribe to daily emails from EarthSky. It’s free!

Visit EarthSky’s Best Places to Stargaze to find a dark-sky location near you.

Post your own night sky photos at EarthSky Community Photos.

Translate Universal Time (UTC) to your time.

See the indispensable Observer’s Handbook, from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada.

Visit Stellarium-Web.org for precise views from your location.

Almanac: Bright visible planets (rise and set times for your location).

Visit TheSkyLive for precise views from your location.

Bottom line: Visible planets and star guide for April 2024. Tonight, watch for the full moon glowing brightly near the also-bright star Spica in Virgo the Maiden.