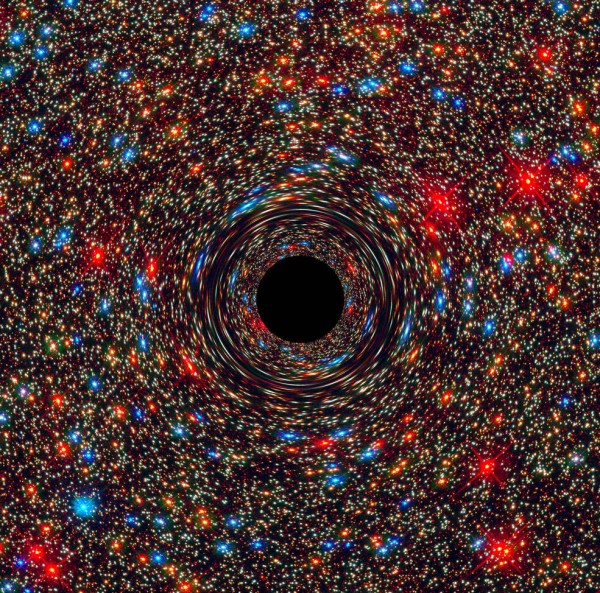

Astronomers uncovered a near-record supermassive black hole – weighing 17 billion suns – in the center of a galaxy in a sparsely populated area of the local universe, about 200 million light-years from Earth in the direction of the constellation Eridanus.

The discovery suggests that supermassive black holes might be more common than once thought, according to a study published April 6, 2016 in the journal Nature.

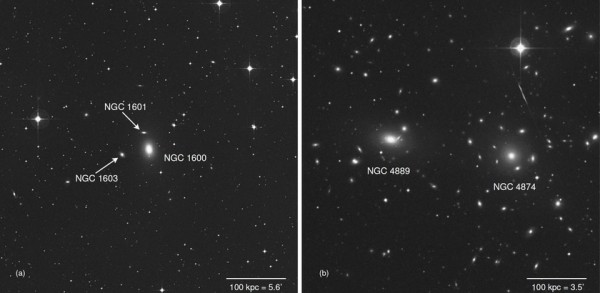

Until now, the biggest supermassive black holes – those with masses around 10 billion times that of our sun – have been found at the cores of very large galaxies in regions loaded with other large galaxies. The current record holder, discovered in the Coma Cluster in 2011, tips the scale at 21 billion solar masses and is listed in the Guinness Book of World Records.

The newly discovered black hole is in a galaxy, NGC 1600, in the opposite part of the sky from the Coma Cluster in a relative desert, said the leader of the discovery team, Chung-Pei Ma, a University of California-Berkeley professor of astronomy, is the leader of the discovery team. She said:

The newly discovered supersized black hole resides in the center of a massive elliptical galaxy, NGC 1600, located in a cosmic backwater, a small grouping of 20 or so galaxies.

While finding a gigantic black hole in a massive galaxy in a crowded area of the universe is to be expected – like running across a skyscraper in Manhattan – it seemed less likely they could be found in the universe’s small towns. Ma said:

Rich groups of galaxies like the Coma Cluster are very, very rare, but there are quite a few galaxies the size of NGC 1600 that reside in average-size galaxy groups. So the question now is, ‘Is this the tip of an iceberg?’ Maybe there are a lot more monster black holes out there that don’t live in a skyscraper in Manhattan, but in a tall building somewhere in the Midwestern plains.

The researchers also were surprised to discover that the black hole is 10 times more massive than they had predicted for a galaxy of this mass. Based on previous surveys of black holes, astronomers had developed a correlation between a black hole’s mass and the mass of its host galaxy’s central bulge of stars – the larger the galaxy bulge, the proportionally more massive the black hole. But for galaxy NGC 1600, the giant black hole’s mass far overshadows the mass of its relatively sparse bulge. Ma said:

It appears that that relation does not work very well with extremely massive black holes; they are a larger fraction of the host galaxy’s mass.

One idea to explain the black hole’s monster size, say the scientists, is that it merged with another black hole long ago when galaxy interactions were more frequent. When two galaxies merge, their central black holes settle into the core of the new galaxy and orbit each other. Stars falling near the binary black hole, depending on their speed and trajectory, can actually rob momentum from the whirling pair and pick up enough velocity to escape from the galaxy’s core. This gravitational interaction causes the black holes to slowly move closer together, eventually merging to form an even larger black hole. The supermassive black hole then continues to grow by gobbling up gas funneled to the core by galaxy collisions. Ma said:

To become this massive, the black hole would have had a very voracious phase during which it devoured lots of gas.

The frequent meals consumed by NGC 1600 may also be the reason why the galaxy resides in a small town, with few galactic neighbors. NGC 1600 is the most dominant galaxy in its galactic group, at least three times brighter than its neighbors. Ma said:

Other groups like this rarely have such a large luminosity gap between the brightest and the second brightest galaxies.

Most of the galaxy’s gas was consumed long ago when the black hole blazed as a brilliant quasar from material streaming into it that was heated into a glowing plasma. Ma said:

Now, the black hole is a sleeping giant. The only way we found it was by measuring the velocities of stars near it, which are strongly influenced by the gravity of the black hole. The velocity measurements give us an estimate of the black hole’s mass.

Enjoying EarthSky? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

Bottom line: Astronomers have found a behemoth black hole in an unlikely place. Astronomers uncovered a near-record breaking supermassive black hole, weighing 17 billion suns, in the center of a galaxy in a sparsely populated area of the universe. The observations may indicate that these monster objects may be more common than once thought.