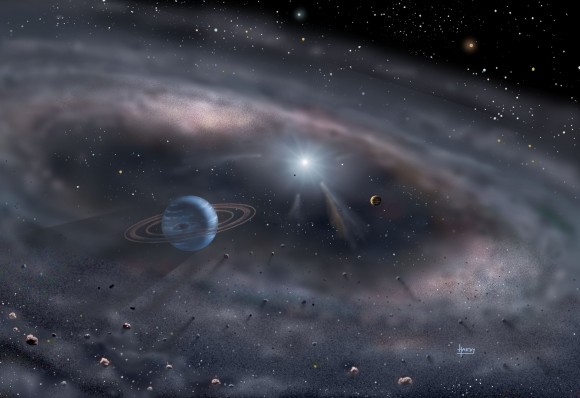

A new study from the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington D.C. offers a potential solution to the question of how small rocky planets like our Earth come to be. A puzzle relates to how dust grains in a disk around a newly forming star avoid being dragged into the star before enough of the grains stick together to have strong-enough gravity to begin pulling in more grains … and ultimately grow into planets. Published in the Astrophysical Journal on June 25, 2015, lead researcher Alan Boss shows in his theoretical study that newly forming stars, called protostars, can scatter small rocky bodies outward during periods of “gravitational instability” in the disk. Boss’ work links this phase of instability with spiral arms now known to exist around some young stars.

According to modern theories about how rocky planets form, during the infant stages of star formation, disks of gas and dust surround protostars. These are called protoplanetary disks. The dust and debris in the disks collide and coalesce, slowly gaining mass and gravity, eventually becoming planetesimals, which are small bodies that fuse with others in order to create planets.

Previous theoretical models have been unable to explain how the planetesimals – mainly those between 1 and 10 meters in radius – resisted being pulled inward and consumed by what’s called gas drag from the star. If too many small bodies are lost to gas drag, there would not be enough left to form orbiting planets.

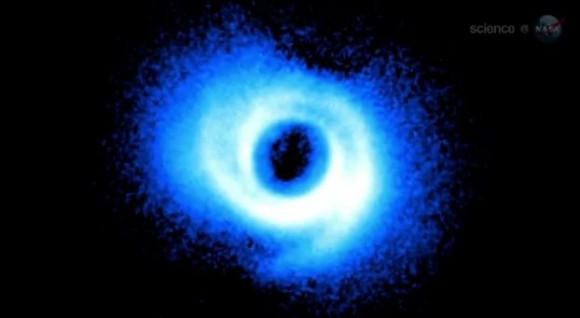

Observations of other young stars reveal that those similar in size to our sun undergo periodic explosive bursts, each lasting about 100 Earth-years. During these outbursts, a star’s luminosity is seen to increase, and astronomers believe the outbursts are linked to a period of “gravitational instability” in the disk.

Boss’s latest work shows that this phase in the life of a newly forming star can scatter the vulnerable 1- to 10-meter bodies outward and away from the star, thereby preventing them from falling into the star and becoming lost.

A statement from Carnegie Institution for Science explained:

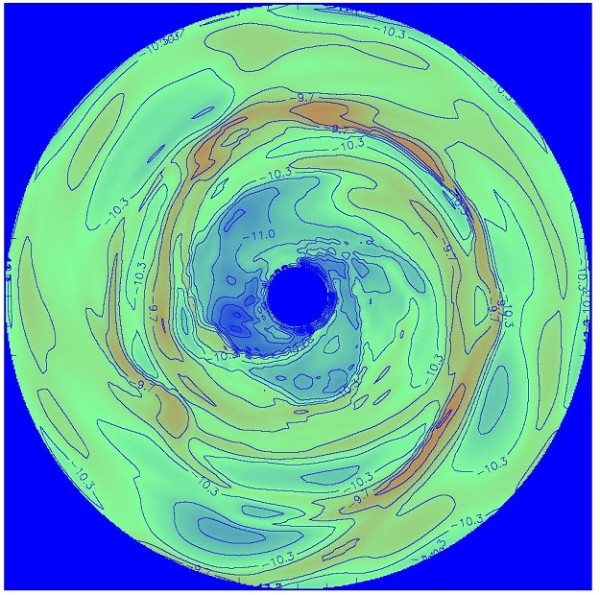

Recent work has shown the presence of spiral arms around young stars, similar to those thought to be involved in the short-term disruptions in the disk.

The gravitational forces of these spiral arms could scatter outward the problematic boulder-sized bodies, allowing them to accumulate rapidly to form planetesimals large enough that gas drag is no longer a problem.

Boss’s modeling techniques hone in on the idea that spiral arms might be able to answer the question of how a developing solar system avoids losing too many larger bodies before the boulders have a chance to grow into something bigger.

Boss added:

While not every developing protostar may experience this kind of short-term gravitational disruption phase, it is looking increasingly likely that they may be much more important for the early phases of terrestrial [rocky] planet formation than we thought.

Boss’ model focuses on the significance of spiral arms and lends a new perspective to the formation of our solar system, as well as solar systems throughout our Milky Way galaxy.

Bottom line: A new theoretical model by Alan Boss of the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington D.C. focuses on the spiral arms now known to exist around some young stars. The spiral arms may enable rocky planets like Earth to form.