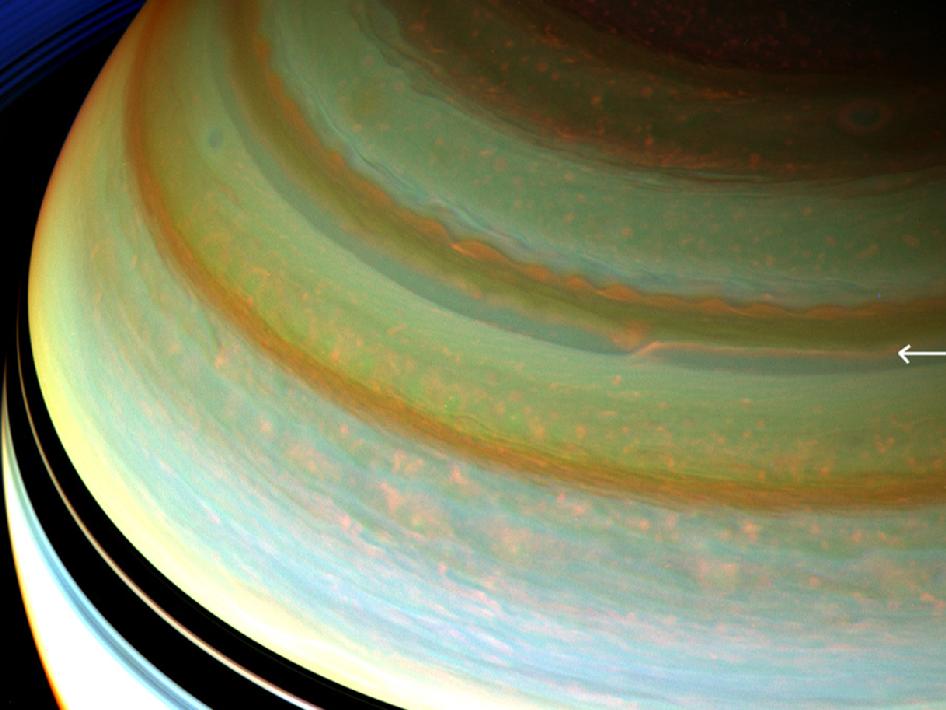

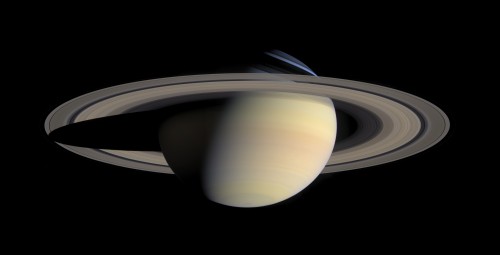

To the human eye, the giant planet Saturn doesn’t appear as colorful – or as distinctly banded – as its neighbor planet, Jupiter. Yet Saturn has bands traveling east and west across its surface, and scientists have come to see them as turbulent jet streams in the atmosphere of this gas giant world. For years, scientists have scratched their heads, trying to understand what energy source drives Saturn’s jet streams. In June 2012, in the journal Icarus, they suggest that heat from within Saturn drives the jet streams.

Saturn’s jet streams are curious and yet reminiscent of earthly jet streams. Most blow eastward on Saturn, but some blow westward. Saturnian jet streams occur in places where temperature varies significantly from one latitude on Saturn to another.

Click here to expand image above

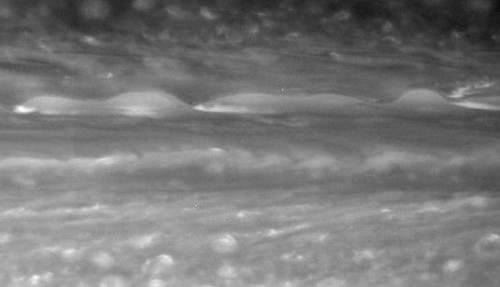

Tony Del Genio of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York is lead author of the June 2012 paper on Saturn’s jet streams and a member of NASA’s Cassini spacecraft imaging team. His group used automated cloud tracking software to analyze the movements and speeds of clouds seen in hundreds of Cassini images from 2005 through 2012. These scientists say that condensation of water from Saturn’s internal heating leads to temperature differences in the atmosphere. The temperature differences create eddies, or disturbances that move air back and forth at the same latitude, and those eddies, in turn, accelerate the jet streams “like rotating gears driving a conveyor belt.”

Tony Del Genio said:

We know the atmospheres of planets such as Saturn and Jupiter can get their energy from only two places: the sun or the internal heating. The challenge has been coming up with ways to use the data so that we can tell the difference.

In other words, a competing theory assumed that the energy for the temperature differences in Saturn’s atmosphere came from our parent star, the sun. In fact, temperature differences in Earth’s atmosphere are driven by sunlight.

But there are profound differences between the atmospheres of Earth and Saturn. For one, Saturn is about 10 times farther from the sun than Earth. Plus Earth’s atmosphere is relatively thin, and lies atop a solid-and-liquid surface. In contrast, Saturn is a gas giant world, with nothing we can meaningfully call a surface.

So the mechanisms that create Saturn’s weather, including its jet streams, need not be the same as on Earth.

Study co-author and imaging team associate John Barbara, also at the Goddard Institute for Space Studies, said:

… we’ve been able to extract nearly 120,000 wind vectors from 560 images, giving us an unprecedented picture of Saturn’s wind flow.

The team’s findings provide an observational test for existing models that scientists use to study the mechanisms that power the jet streams. In this way, they were able to pin down Saturn’s internal heat as the energy source of the planet’s jet streams.