The Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania is well known for hominin fossils – including those of early human ancestors – that have shaped our understanding of human evolution. In a new study, reported in the March 15, 2016 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, paleoanthropologists used ancient evidence — fossil remains of hominins, animals and plants, as well as primitive tools made by hominids — to build a vivid description of what life was like for our early human ancestors, 1.8 million years ago.

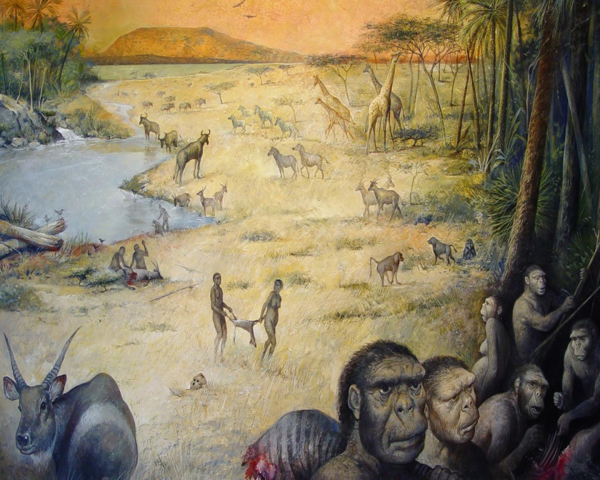

If we could travel back in time to that Olduvai Gorge site, we would have walked through a woodland patch with palm and acacia trees to a small fern-laced freshwater wetland fed by a spring. Around this little oasis stretched open grasslands where giraffes, elephants and wildebeests roamed. Not as obvious were the predators lurking nearby: lions, leopards and hyenas.

Gail M. Ashley, a professor at the Rutgers University Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, said in a statement:

We were able to map out what the plants were on the landscape with respect to where the humans and their stone tools were found,. That’s never been done before. Mapping was done by analyzing the soils in one geological bed, and in that bed there were bones of two different hominin species.

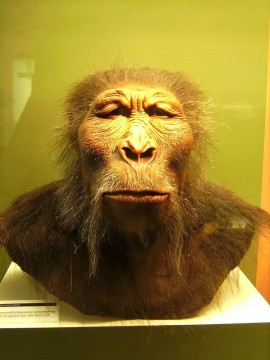

She’s referring to two species of hominins, both with ape- and human-like features, that were about 4.5 to 5.5 feet tall, with a lifespan of 30 to 40 years. Paranthropus boisei had a robust build with small-brains. Homo habilis, thought to be more closely related to modern humans, was a lighter-boned hominin with a larger brain.

Both species had used the site for a long time, perhaps as much as hundreds of years, for food and water, but may not necessarily have lived there.

Ashley explained that the rich trove of remains, including bones bearing cuts from primitive tools, were well-preserved due to ash from a volcano about 10 miles (15 km) away.

Think about it as a Pompeii-like event where you had a volcanic eruption. The eruption spewed out a lot of ash that completely blanketed the landscape.

Piecing together different aspects of the hominins’ habitat helps paleoanthropologists develop models that reconstruct the lives of our early human ancestors. What were they like? How did they live and die? What kind of behavior did they display? What did they eat?

Said Ashley, who has been studying the area since 1994:

It was tough living. It was a very stressful life because they were in continual competition with carnivores for their food.

The hominins themselves were also at risk of attack by lions, leopards and hyenas that stalked the land.

Her team found high concentrations of animal bones in sections that were once woodlands, suggesting that the hominins retreated into the relative safety of the woods to eat meat off the carcasses. They may have also eaten crustaceans, snails and slugs, as well as vegetation like ferns, in the wetlands.

Ashley commented:

[Paleoanthropologists] have started to have some ideas about whether hominins were actively hunting animals for meat sources or whether they were perhaps scavenging leftover meat sources that had been killed by say a lion or a hyena.”

The subject of eating meat is an important question defining current research on hominins. We know that the increase in the size of the brain, just the evolution of humans, is probably tied to more protein.

Bottom line: Scientists have reconstructed what a hominid habitat from 1.8 million years ago might have looked like. At a site in the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, they discovered evidence that there was once a small patch of woods, freshwater wetlands and a spring, all surrounded by grasslands. Animals such were giraffes, elephants and wildebeests were present, as well as lions, leopards and hyenas. Such information helps scientist better understand what life was like for our early human ancestors.