With a major conference on Arctic governance due to convene in Toronto on January 17-18, 2012, Arctic politics are in the news. The 2nd annual Munk-Gordon Arctic Security Conference has attracted the participation of several experts, national ambassadors and indigenous leaders – more than 100 participants from 15 nations in all – according to a press release issued yesterday (January 15, 2012) by the Arctic Council. On the agenda is the inclusion in the Arctic Council of countries that do not border the Arctic. According to the release:

… countries like China, India and Brazil, which have no Arctic territories, are nonetheless knocking on the door of the increasingly influential Arctic Council looking for admission as permanent observers.

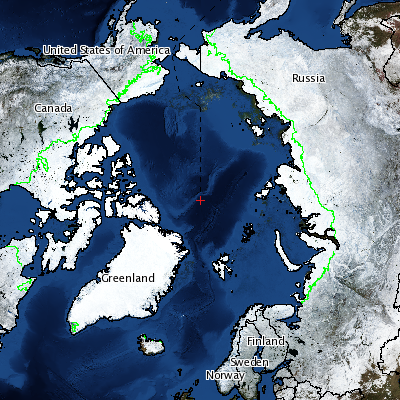

Why do they want to join? The Arctic is rich in resources, such as oil, gas, minerals, fresh water and fish, increasingly tourism, and – if the subarctic is included – forests. In times past, the Arctic was in mostly accessible to all but the small indigenous populations that lived there. It was an ice-covered ocean, a driver of Earth climate, a place for early 20th century explorers to make a name for themselves.

But that old view of the Arctic has changed. The sizable Arctic resources have become more accessible in our time due to advances in technology, the economic opening up of Russia (whose northern border is in the Arctic), and last but not least climate change, which is expected to make the Arctic ice-free in the summertime sometime in this century.

A year ago, EarthSky interviewed imminent oceanographer Sylvia Earle, who was one of 11 members of the Commission on Arctic Climate Change, which released its report on the Arctic – called The Shared Future – in early 2011. She told us:

The Arctic has a disproportionate impact on the world given its relatively small size. This is a moment in history when we will take actions one way or the other – or inactions – but we humans will influence much that determines the fate and future of the Arctic, the people and the creatures who live there. And in so doing, we have a global impact on all people everywhere.

In other words, what happens in the Arctic in the next few decades will affect the whole globe. Still, it’s in some ways understandable that some long-time Arctic Council members are reluctant to include non-Arctic nations, since the needs and issues of those nations bordering the Arctic are surely very specific. According to yesterday’s press release, Russia and Canada are most strongly opposed to non-Arctic nations’ participating in the Arctic Council. Canada is preparing to assume the chair of the Council in 2013, and, by the look of things, this issue will be one Canada and the Council as a whole will be grappling with for some time.

The Arctic Council was established in 1996 as “a high level intergovernmental forum,” according to its website. Full members of the Arctic Council are Canada, Russia, the United States, Norway, Finland, Sweden, Iceland and Denmark (Greenland) – the eight countries with Arctic territory. Six northern indigenous groups – the Inuit Circumpolar Council, Arctic Athabaska Council, Gwich’in Council International, Sami Council, Russian Association of the Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) and Aleut International Association – wield strong influence as permanent participants. Another six non-Arctic nations sit in as observers today: the U.K., France, Germany, Spain, Poland and the Netherlands.

In addition to China, India and Brazil, other non-Arctic nations – including Japan, South Korea, the European Union and several individual European states – now want “observer” status on the Arctic Council. Tony Penikett, Special Advisor to the Munk-Gordon Arctic Security Program and former Premier of the Yukon, said:

The Council is struggling with this question. The non-Arctic states’ interest is not just a fleeting fancy. For the Council to remain relevant, must it give them a larger role or remain an exclusive club?

Bottom line: India, China, Brazil, Japan and other countries want a seat as “observers” on the Arctic Council. This issue will be on the Council’s agenda during the 2nd annual Munk-Gordon Arctic Security Conference, which will meet in Toronto on January 17-18, 2012.