A big and hopeful thing happened at the end of last week in the area of fake news. On March 9, 2018, the largest-yet study of fake news was published in Science. Accompanying it was a second article in Science, in which scientists called for:

… interdisciplinary research to reduce the spread of fake news and to address the underlying pathologies it has revealed.

The large study is titled The Spread of True and False News Online. Soroush Vosoughi of MIT was its lead author, working with co-authors Deb Roy and Sinan Aral. All of these researchers work in MIT’s Laboratory for Social Machines; that is, they’re trained to study and ultimately understand what most of us find unfathomable, the spread of information online. They found that:

Falsehood also diffused faster than the truth. The degree of novelty and the emotional reactions of recipients may be responsible for the differences observed.

They explained their study in its abstract:

We investigated the differential diffusion of all of the verified true and false news stories distributed on Twitter from 2006 to 2017. The data comprise ~126,000 stories tweeted by ~3 million people more than 4.5 million times. We classified news as true or false using information from six independent fact-checking organizations that exhibited 95 to 98% agreement on the classifications. Falsehood diffused significantly farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth in all categories of information, and the effects were more pronounced for false political news than for false news about terrorism, natural disasters, science, urban legends, or financial information. We found that false news was more novel than true news, which suggests that people were more likely to share novel information. Whereas false stories inspired fear, disgust, and surprise in replies, true stories inspired anticipation, sadness, joy, and trust. Contrary to conventional wisdom, robots accelerated the spread of true and false news at the same rate, implying that false news spreads more than the truth because humans, not robots, are more likely to spread it.

Meanwhile, in the second Science article – titled The Science of Fake News – David M. J. Lazer and 15 other social scientists and legal scholars called for more interdisciplinary study of fake news. More studies, and studies between disciplines, will be an important early step in understanding fake news, in helping people to learn to recognize it, and, hopefully, in helping to reduce it. Lazer is a professor of political science and computer and information science, and is co-director of Northeastern University’s NULab. He and his colleagues write that:

Internet platforms have become the most important enablers and primary conduits of fake news. It is inexpensive to create a website that has the trappings of a professional news organization. It has also been easy to monetize content through online ads and social media dissemination. The internet not only provides a medium for publishing fake news but offers tools to actively promote dissemination.

The group points out that, on the internet today, websites can operate relativity cheaply in contrast to in the past, where information had to be printed in monthly magazines or daily newspapers or, as in the particular case of EarthSky, for example, disseminated via radio. Some readers might not realize the extent to which small, privately owned websites like EarthSky can say … well … anything. If we at EarthSky wanted to say the moon is made of green cheese, we could. In the 20th century, that statement wouldn’t have flown. Saying it would have put us in the fringe group category. But in today’s anything-goes world of information overload, if we said it often enough, convincingly enough, with good charts and illustrations, with quotes from known historical figures saying it (taken out of context, naturally) – with glaring news headlines making outrageous claims that don’t really match reality (or even always match what’s being said in the article below the headline) – a portion of our audience might begin to believe it. Some portion of those believers might become devoted followers of our moon-as-green-cheese stories, in which case they’d spread our stories via their own social media outlets. We might become a moon-as-green-cheese community online, a place where, in our comments sections, people would suggest that non-believers should “wake up,” and see our (distorted) light.

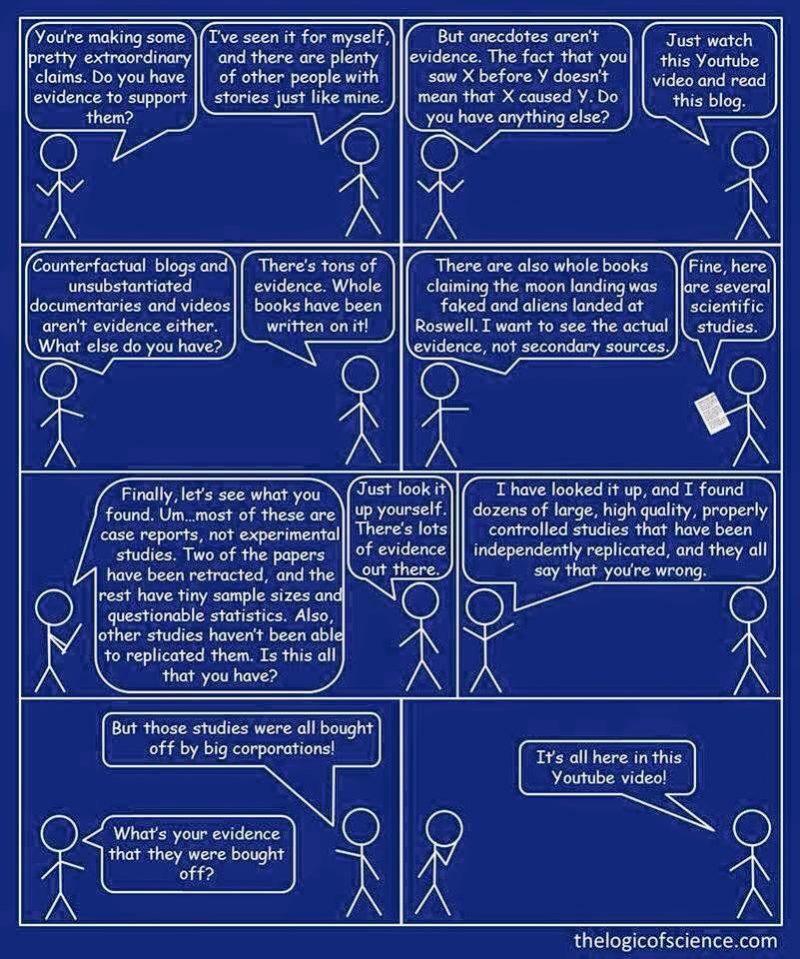

People do form communities online around fake news. That’s because, as Lazer and his colleagues point out in their article:

Research also further demonstrates that people prefer information that confirms their preexisting attitudes (selective exposure), view information consistent with their preexisting beliefs as more persuasive than dissonant information (confirmation bias), and are inclined to accept information that pleases them (desirability bias). Prior partisan and ideological beliefs might prevent acceptance of fact checking of a given fake news story.

Search engines like Google helpfully promote people’s preferences. If you believed the moon was made of green cheese, say, and read articles on that subject, search engines like Google are programmed to show you more of the same, truth or falsehood notwithstanding.

A first step in future academic studies of fake news will be to define key terms. Lazer and colleagues’ Science article was discussed in a March 9 article in The Atlantic, titled Why It’s Okay to Call It “Fake News”. The Atlantic article primarily discussed the question of whether fake news or false news is the preferred term. As academic studies proceed, those sorts of terms will come to be defined.

Fake news itself will be clearly defined. Lazer’s article said:

We define “fake news” to be fabricated information that mimics news media content in form but not in organizational process or intent. Fake-news outlets, in turn, lack the news media’s editorial norms and processes for ensuring the accuracy and credibility of information. Fake news overlaps with other information disorders, such as misinformation (false or misleading information) and disinformation (false information that is purposely spread to deceive people).

Lazer’s article very interestingly traces some of the history of media across the last century, saying:

Journalistic norms of objectivity and balance arose as a backlash among journalists against the widespread use of propaganda in World War I (particularly their own role in propagating it) and the rise of corporate public relations in the 1920s.

Like all things, media evolves. Lazer’s team wrote:

… Failures of the U.S. news media in the early 20th century led to the rise of journalistic norms and practices that, although imperfect, generally served us well by striving to provide objective, credible information. We must redesign our information ecosystem in the 21st century. This effort must be global in scope, as many countries, some of which have never developed a robust news ecosystem, face challenges around fake and real news that are more acute than in the United States. More broadly, we must answer a fundamental question: How can we create a news ecosystem and culture that values and promotes truth?

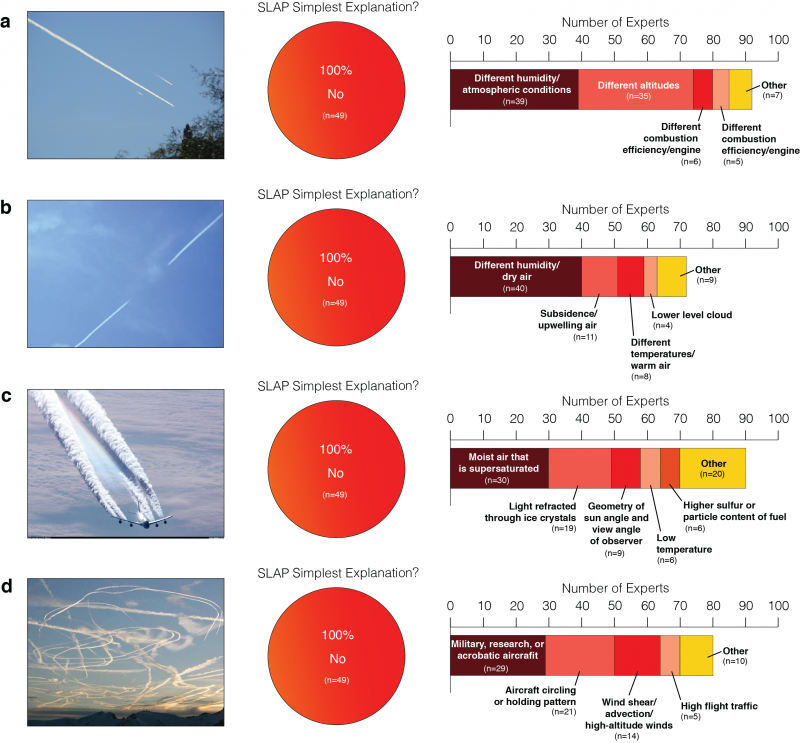

Most fake news stories center on politics, by the way, but science news has its fake stories, too, with the best-known one, probably, being the nefarious so-called “chemtrails.” You might know of people who believe that the ordinary contrails left by jet aircraft are these “chemtrails,” part of a vast, secret, global conspiracy to … what? The described purpose has morphed and changed over the years, but currently most “chemtrails” believers will tell you that Earth’s climate is being secretly and deliberately engineered (to make it hotter? colder? I’ve never been clear on why, and I’m not sure if all chemtrail-believers agree).

As with all good lies, the chemtrails conspiracy theory contains its grain of truth. There are indeed historical references to geoengineering and weather modification among scientists. Modern scientists continue to use the term geoengineering to describe the idea of deliberately altering Earth’s climate, in case global warming becomes so severe that nations agree on a need to implement drastic action.

And drastic, indeed, it would be. Earth’s climate is vast and complicated, with many feedbacks. All climate scientists known that any intentional program to alter Earth’s climate could be expected to have unintended consequences. However, as scientists tend to do, they discuss it. They study it. There was one small-scale geo-engineering experiment, via high-altitude balloon, announced last year. One of its lead scientists – David Keith at Harvard – told me by email today:

Nothing has happened yet. I think there’s about a 50/50 chance we end up flying this year.

Meanwhile, a 2016 survey of 78 atmospheric scientists overwhelmingly showed that the so-called “proof” for “chemtrails” is not proof at all.

I’m beginning to think that people who believe in things like “chemtrails” (and also “the moon landings were a hoax,” for example) are truly brainwashed, not in the sense of being forced to believe, but in the sense of having absorbed an overflow of false information. There’s an interesting film about this sort of brainwashing called The Brainwashing of My Dad by Jen Senko. I highly recommend it, if you’re interested in this phenomenon.

How to separate truth from fiction? Fake news is a powerful crisis of our time, and I’m glad scientists are calling for studies.

Bottom line: Science publishes the largest-yet study of fake news and a call for more studies by 16 social scientists and legal scholars. Plus, a word about so-called “chemtrails.”

Source: The spread of true and false news online

Source: The science of fake news

Read more: Atmospheric scientists say ‘no chemtrails’

Read more: Solar geoengineering and the chemtrails conspiracy on social media