Not all spiders weave webs to trap their prey. Some species in South America and New Zealand, known as trap-jaw spiders, have unusual mouth structures that clamp down on their quarry, like a mousetrap, at lightning speeds. In a recent study, scientists found that these tiny inconspicuous arachnids strike their prey with a burst of power that’s stronger than what their muscles can muster, suggesting another mechanism used to store and release the needed power. These findings were published online in April, 2016, in the journal Current Biology.

Smithsonian scientist Hannah Wood, the lead author of the paper, said in a statement:

This research shows how little we know about spiders and how much there is still to discover.

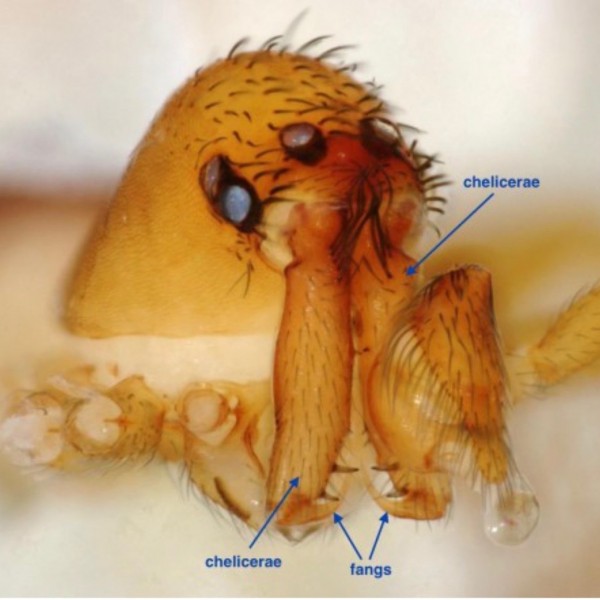

The trap-jaw spiders in the study belong to the Mecysmaucheniidae taxonomical family of spiders. These tiny well-camouflaged spiders, that have highly maneuverable mouth parts called chelicerae, hunt on the forest floor.

They stalk their prey with their mouth wide open and when they get close enough, their jaws snap shut on the prey at lightning speed.

High speed videos of the spiders show the power and swiftness of the spiders’ chelicerae. The fastest of the 14 Mecysmaucheniidae species that were studied required a recording speed of 40,000 frames per second. The slowest spider species was just 100 times slower, still impressive considering their size.

The amount of power released in that final snap-down cannot be accounted for by muscle power alone. Another mechanism is responsible for the relatively large amount of power that’s unleashed. This phenomena, known as “power amplification,” has only been observed in some ant species that evolved the fastest-moving mouth parts known in animals. This is the first time power amplification has been seen in spiders.

DNA analysis on this group of spider species indicates that their similar specialized mouth parts evolved independently at least four different times; this phenomena is known as convergent evolution where organisms independently evolved similar features from living in similar environments.

Wood and her team plan to do follow-up studies to better understand the source of power that’s stored, then released for the spiders’ super-fast mouth movements, and why they evolved this capability.

Said Wood, in the same statement:

Many of our greatest innovations take their inspiration from nature. Studying these spiders may give us clues that allow us to design tools or robots that move in novel ways.

Bottom line: Scientists have discovered several spider species from South America and New Zealand with mouth parts that move with lightning speed to snap down on prey like a mousetrap. The relatively enormous power needed for the super-fast mouth movements cannot be executed by muscles alone, indicating that the spiders evolved another mechanism to releases that power.