Originally published on May 4, 2022, at The Conversation. The author is wildfire scientist Molly Hunter at the University of Arizona. She explains what’s fueling the extreme fire conditions and why risky seasons like this are becoming more common. Editors at EarthSky have provided some links to updated information and resources.

Fire season started early this year in US Southwest

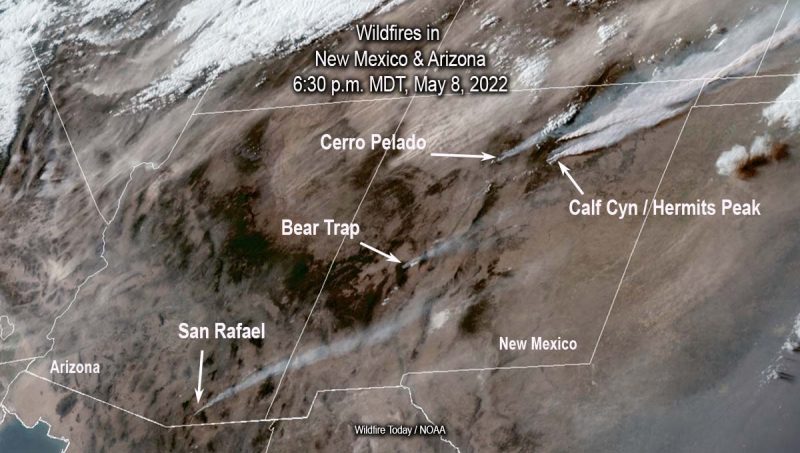

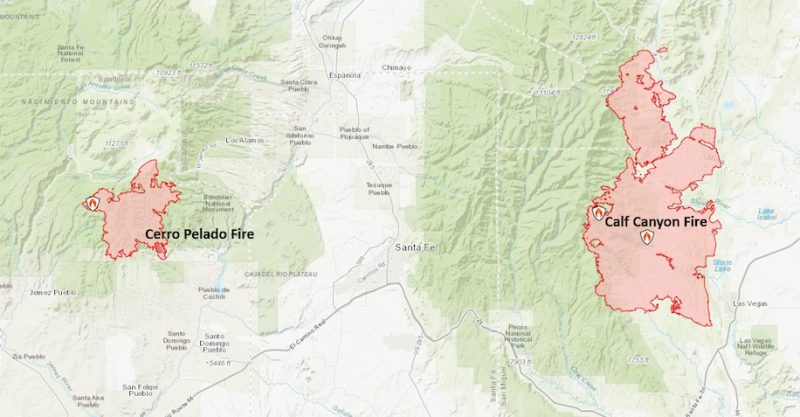

New Mexico and Arizona are facing a dangerously early fire season. Neighborhoods are already in ashes, with effects so devastating that U.S. President Joe Biden issued a disaster declaration for New Mexico on May 4, 2022. By early May, over 600 fires had broken out in the two states. And large wildfires burned through hundreds of homes near Ruidoso and Las Vegas, New Mexico, and Flagstaff, Arizona.

Historically, fire season in the Southwest doesn’t ramp up until late May or June because fuels that carry fires – primarily woody debris, leaf litter and dead grasses – don’t fully dry out until then.

Now, the U.S. Southwest sees more fires start earlier in the year. The earlier fire season is partly due to the warming climate. As temperatures rise, snow melts more rapidly, more water evaporates into the atmosphere and the grasses and other fuels dry out earlier.

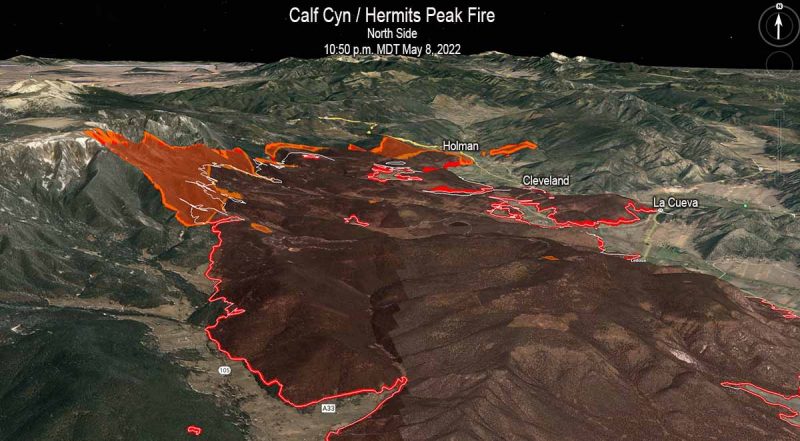

CNN on May 9: An extremely critical, highest-level fire risk has been issued near the Calf Canyon/Hermits Peak Fire, as powerful winds, combined with exceptional drought conditions, threaten to fuel the largest wildfire now burning in the United States.

From the Washington Post on May 8: Winds fuel New Mexico wildfire, complicating containment efforts

Strong winds drive rapid fire growth

Unfortunately, the earlier timing coincides with when the region experiences strong winds that drive rapid fire growth. Some of the fires we see this year, like the Tunnel Fire near Flagstaff and the fires in New Mexico, are driven by these really intense wind events. They’re pretty typical winds for spring. But fuels are now really dry and ready to burn.

This year, we also have a lot of fuel to burn. Last summer, in 2021, the U.S. Southwest had an exceptional monsoon season that left green hillsides and lots of vegetation. By now, the grasses and forbs that established during the monsoon have dried out, leaving a lot of biomass that can carry a fire. Our biggest fire years come when we have a wet period followed by a dry period, like the La Niña conditions we’re experiencing now.

Warmer climate means longer fire season

In the U.S. Southwest, climate change means warmer, drier conditions. One immediate effect is the lengthening of the fire season.

We see fires starting in March and April. And if the U.S. Southwest doesn’t get a good summer monsoon, fire season won’t really stop until we get significant rainfall or snowfall in fall and winter. That means more stress on firefighting resources, and more stress on communities facing fire, smoke and evacuations.

As fire season lengthens, states are also seeing more fires caused by human activities, such as fireworks, sparks from vehicles or equipment, and power lines. More people are moving out into areas that are fire-prone, creating more opportunities for human-caused ignitions.

When fires burn in areas that didn’t see fire historically, they can transform ecosystems.

If you have been affected by fire, you can go to disasterassistance.gov to apply for aid. Or you can call 1-800-621-3326 to get started. Those with insurance should file a claim with their own insurance companies first, before starting the process with FEMA.

Grasses are fueling wild fires

People generally don’t think of fire as being a natural part of desert ecosystems, but grasses are now fueling really big fires. These fires spread farther, and into different ecosystems. The Telegraph Fire started in a desert system, then burned through chaparral and into the mountains, with pine and conifer forest.

Part of the problem is that invasive grasses like buffelgrass and red brome spread quickly and burn easily. A lot of grass is now growing in those desert systems, making them more prone to wildfire.

Invasive buffelgrass is a threat to desert ecosystems and communities.

Some plants can’t survive a wildfire

When a fire spreads in the desert, some plant species, like mesquite and other brushy plants, can survive. But the saguaros – the iconic cactus that are so popular in tourist visions of the U.S. Southwest – are not well adapted to fire, and often die when exposed to fire. Paloverde trees are also not well adapted to survive fires.

What does come back quickly is the grasses, both native and invasive. So, in some areas we see a transition from desert ecosystem to a grassland ecosystem that is very conducive to the spread of fire.

The Cave Creek Fire near Phoenix in 2005 is an example where you see this transition. It burned over 240,000 acres, and if you drive around that area now, you don’t see lot of saguaros. It doesn’t look like desert. It looks like more like annual grassland.

The desert is an iconic landscape, so the loss affects tourism. It affects wildlife as well. A lot of species rely on saguaros for nesting and feeding. Bats rely on the flowers for nectar.

Sadly fire season is inevitable

In some respects, people have to recognize that fire is inevitable.

Fires quickly surpass our capacity to control them. When winds are strong and the fuels are really dry, there’s only so much firefighters can do to prevent some of these big fires from spreading.

What can help reduce an intense fire season?

Conducting prescribed fires to clear out potential fuel is one important way to lessen the probability of big, destructive blazes.

Historically, far more money went into fighting fires than managing the fuels with tactics like thinning and prescribed fire. But the infrastructure bill signed in 2021 includes a huge influx of funding for fuels management. There’s also a push to move some seasonal fire crew jobs to full-time, yearlong positions to conduct thinning and prescribed burns.

Homeowners can also be better prepared to live with fires. That means maintaining yards and homes by removing debris so they’re less likely to burn. It also means being prepared to evacuate.

If you have been affected by fire, you can go to disasterassistance.gov to apply for aid. Or you can call 1-800-621-3326 to get started. Those with insurance should file a claim with their own insurance companies first, before starting the process with FEMA.

Bottom line: The 2022 fire season started early and is intense. Using prescribed burns and thinning can help reduce how quickly and far a wildfire spreads.

Small temperature increase can cause bigger wildfires, more often