EarthSky’s once-a-year fundraiser going on now. Please donate to help us keep going!

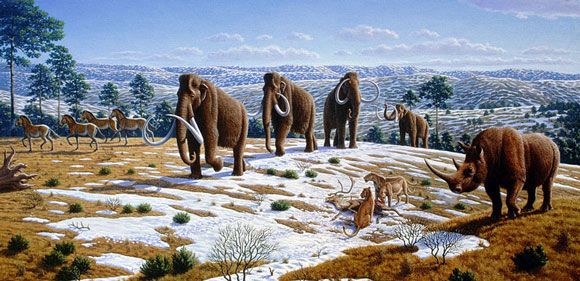

The extinction of large herbivores such as woolly mammoths, mastodons, and giant ground sloths during the late Pleistocene epoch likely substantially altered landscapes across the world, scientists say. Those herbivores, which fed on sprouting trees and shrubs, played a key role in maintaining open landscapes. Once they disappeared, dense woody vegetation became much more abundant. The new study was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on January 26, 2016.

The Pleistocene epoch, which spanned from 2,588,000 to 11,700 years ago, was marked by several cold glacial cycles, and it ended as the Earth warmed. From about 80,000 years ago to the end of the Pleistocene, many large herbivores went extinct. Those herbivores included animals such as woolly mammoths, mastodons, and giant ground sloths. Their extinction was driven by both changes in the climate and over hunting by early humans.

Pollen records from this geological time period show that the abundance of woody plants increased in many areas that were once open landscapes. While climate change certainly played a role in this transition, the large-scale alteration of landscapes was also likely facilitated by the loss of the large herbivores. When the herbivores roamed the Earth, they suppressed woody vegetation by feeding on sprouting shoots and leaves. Once they went extinct, this grazing pressure was removed from the landscape and woody plants were able to flourish.

Elisabeth Bakker, lead author and senior scientist at the Netherlands Institute of Ecology commented on the findings in a press release. She said:

Large herbivores are not merely victims of the circumstances they live in, but actively engineer their environment. This has major consequences for other species, and for the structure of the entire landscape. Acknowledging the major ecosystem-engineering role of large herbivores, you can’t imagine that vegetation stayed the same regardless of their presence or absence in the Late Pleistocene.

In the paper, the scientists present several pieces of modern evidence in support of their hypothesis that the loss of large Pleistocene herbivores changed the abundance of woody plants and, ultimately, the landscape. This evidence comes from exclusion experiments where animals such as moose and deer were prevented from grazing on young trees. In exclusion zones, woody vegetation flourishes. The video below shows some good images of these landscape changes. Check it out!

Now that they have established a conceptual framework for how landscapes can be altered by large herbivores, the authors are hoping to collect more pollen and fossil data from particular landscapes to get a more detailed look at the timings of extinctions and changes in the vegetation.

Co-authors of the study included Jacquelyn Gill, Christopher Johnson, Frans Vera, Christopher Sandom, Gregory Asner, and Jens-Christian Svenning.

Bottom line: The extinction of large Pleistocene herbivores changed the abundance of woody plants and, ultimately, the landscape, scientists say. The new study was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on January 26, 2016.

What killed the woolly mammoth? New clues.

Real Paleo diet: Early hominids ate just about everything

Alligator holes benefit Everglades fish, snakes, turtles, birds