Today’s vocabulary words are:

Paleoparasitology: The study of parasites found in archaeological or paleontological material.

Coprolite: Fossilized dung.*

Let’s use them in a sentence shall we: A landmark in paleoparasitology occurred last week when scientists announced the discovery of tapeworm eggs in a 270 million-year-old shark coprolite.

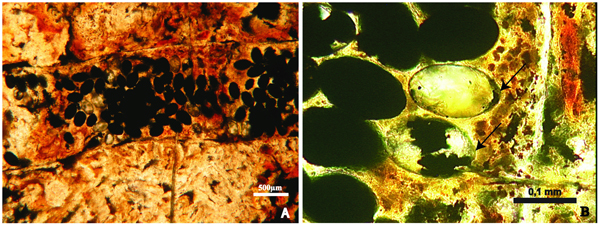

It’s true. While sifting through a crop of coprolites unearthed in what is now southern Brazil, researchers noticed that one contained a cluster of 93 eggs, including an egg that appears to be sporting a partially developed tapeworm larva. Neat?

Plenty of children dream of digging up dinosaurs bones when they grow up, but few likely extend such ambitions to visions of carefully slicing through pre-historic poo to find evidence of intestinal parasites. They should perhaps consider reworking their fantasies. Tapeworms are a rarer find than dinosaurs. They’re small and soft bodied and don’t preserve well. And as we go further back in time, remnants of intestinal parasites become increasingly scarse.

This new discovery is the earliest record of tapeworms yet, dating back to the mid to late Permian period. How old is that? Well, the earth’s landmass was still combined into a single continent known as Pangaea, and was tens of millions of years away from seeing its first dinosaurs. So yeah, pretty old.

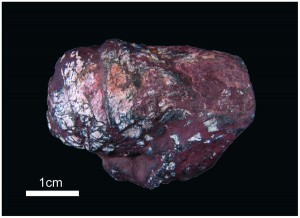

Having only eggs and crap to work with, it was impossible for scientists to determine the exact species of either the parasite or its host, but they were able to draw some conclusions further up on the taxonomical hierarchy. They attribute the coprolite to some kind of shark due to its spiral shape – a characteristic trait of items emerging from a sharky digestive tract.

As for the eggs, their identity was deduced in part by their shape but also by the way they were distributed. Tapeworms are fascinating animals. And by fascinating, I mostly mean disgusting. After being inadvertently swallowed by its host, a tapeworm attaches to the host’s intestinal lining with its head (aka scolex). Because it leaches pre-digested nutrients from its host, a tapeworm doesn’t need its own digestive system. Instead it devotes itself to growing out its body in segments called proglottids, each of which contain their own reproductive organs. Eggs are deposited into these proglottids, and the ones at the tail end of the animal break off like some kind of parasitic escape pods ferrying their precious eggs out of the host via its feces. The eggs found in the shark coprolite are arranged in just the kind of dense cluster one would expect from a tapeworm.

Our modern day tapeworms often require multiple hosts to complete their repulsive lifecycles. For aquatic species, eggs may mature in the water, where they are eaten by small fish or crustaceans, which are in turn eaten by larger fish (and sometimes eventually humans). Along with its bounty of eggs, the shark coprolite also contained scales and bone fragments, indicating that the shark could have picked up its parasite from an earlier meal. Additionally, the fossil poo was part of a large grouping of other coprolites (about 500) found in a relatively small area – possibly a pond whose residents had been cut off from a larger body of water during a dry spell. Crowded conditions are great for spreading parasites.

And let’s not forget that larva like blob in one of the eggs. While still not developed enough to narrow down to species level, it did have some “fiber-like objects” that the researchers think could be nacent hooks. You know, for latching onto unsuspecting hosts and stealing their food.

It’s important to keep in mind that the rarity of parasites from early geological periods doesn’t necessarily mean that there were fewer parasites around back then. As mentioned, they’re not the easiest organisms to find. Tapeworms are great at what they do. They’ve figured out how to thrive within their hosts without killing them off or otherwise attracting unwanted attention to themselves (tapeworm infections in humans sometimes go years without detection). They’ve likely been honing their skills for some time, perhaps for as long as there have been available hosts to get their hooks into.

* Bonus vocabulary: the fossilized poo of human animals prefers to be addressed as “paleofeces”.